City and nature as a theater of permanent conflict between society and government

The problem of conflict and tension in the social and political dimension of the Russian urban and natural environment is important for understanding the context in which the process of the opposition of public organizations acting from anti-authoritarian positions and authoritarian power in Russia takes place. Productive disclosure of the problem is served by two concepts — “public space” and “civil society”, directly related to each other. Their actualization, in relation to the modern Russian context of social and political movements in the second half of the 2010s and early 2020s, is the subject of our new article. The example of two cases of success of civil society from the recent history of the protest movement, not directly related to the political situation and political demands (the situation around the plans to create a landfill in Shies and the environmental protest around it, the struggle for the status of St. Isaac’s Cathedral, against its transfer to the Russian Orthodox Church — for its preservation as a historical museum) the paper shows how the struggle of civil society with the authorities for public space (“the right to the city” and “the right to nature”) has become the main motive in relations between government and society, the motive of anti-authoritarian resistance of society to authoritarian power during the rise of the dictatorship.

The history of the term “public space”, whose importance in describing the modern relations between society and power, can hardly be overestimated, in its origins, refers to the names of two prominent representatives of political and philosophical thought of the second half of the twentieth century, Hannah Arendt and Jurgen Habermas. But if the former understands “public space” as a kind of “arena for the actions of people committed by them in front of each other”1, public space naturally goes back to the ancient Greek “agora”, the meeting place for all free residents of the policy. In other words, in this view, public space is a direct physical place (for example, a city square at the time of a meeting or rally), which accommodates a large number of people carrying out the process of communication on significant problems and issues for society. In the concept of the latter, the very term of “public space” (or rather, “public sphere”) is revealed through the basic concept for its theory, through the concept of “communicative action”2. We can say that in the Habermasian sense, public space is communication itself, as such, wherever it takes place, not necessarily localized in a specific material place. For example, in our time, a virtual platform can also be used for discussion: Internet forums, accounts of political or public figures on social networks, or pages and groups of political and public movements or specific upcoming public events and civil protests, calls for signing various kinds of petitions with demands and appeals to the authorities, and so on. Public space in the modern world, therefore, may well be not only real but also virtual.

Another distinctive aspect of the ideas of Arendt and Habermas is that the former associated “public space” with a certain bright act that acts as a constitutive basis for it (for example, a city square becomes a public space, at the moment a single picket is held on it, caused by the actual currently a problem that attracts public attention). And the latter connected publicity with discursive utterance as such. For Habermas, “public space” is constituted by the discursive practice itself, and not by any real or actual act3. In our opinion, it seems to be the right step to use both of these concepts on absolutely equal grounds as a theoretical foundation that contributes to the productive disclosure of the topic raised in our article.

The second extremely important concept for us, as already mentioned, is the concept of “civil society”. Discussions and disputes about the presence or absence of civil society in our country have been going on throughout, without exception, the entire post-Soviet history. Some believe that it is at least premature to speak of the existence of civil society in our country4, especially in the sense it is understood by Western countries with a long history of democratic development. Others believe that, despite all the unconditional differences with Western societies, we can nevertheless declare that Russia has its analog of civil society5. A well-known difficulty in constructing a parallel between civil society in Western (and not only Western) democratic countries and in Russia is added by the fact that being transferred to Russian realities, this concept itself sometimes turns out to be confusingly identified and localized in the phenomenon of “intelligentsia”, as a specific social stratum, characteristic of the Russian historical and cultural context, people of intellectual labor, publicly articulating their civil and moral position. And here we face an equally important topic, the topic of relations between the intelligentsia and the authorities, in which two mutually exclusive vectors are observed.

In one case, the state, which was “more and more subservient to the private interests of the groups that privatized it, ceasing to be a system of public institutions based on the law and turned out to be quite compatible with closed informal structures,” acquired the features of a community closed from the rest of society, like a mafia group, naturally gave rise to the reaction of civil society, which was expressed in the creation of independent public organizations, whose activity was to expose the numerous cases of abuse of state bodies and among civil servants6. And in the second case, the authorities made attempts (sometimes, it should be noted, quite successful) to saddle the request of the most progressive part of society, directing the sporadic efforts of various kinds of social activists to humanize the social sphere in a centralized, but most importantly, safe and acceptable channel7.

After the protest activity of 2011-2012 the Putin regime, already bypassing any remnants of constraint, declared war on any form of social activity that it was not able to subjugate or bring under its control. This process took place against the background of an ideological turn in the rhetoric of the regime, the so-called “conservative turn”8, accompanied by an attack on liberal values, as well as on Western civilization as such, appeals to the so-called. “traditional values of Russian statehood”. This culminated in the annexation of Crimea, and then the “hybrid war” in southeastern Ukraine. In addition to the obvious task of expansion, Putin’s aggressive foreign policy pursued among its goals the whipping up of chauvinistic hysteria in the public mind, and the consolidation of society in permanent patriotic “rallies around the flag.” The result was a strategy of power aimed at appropriating any form of social and humanitarian initiatives, subordinating them to the “general political line”, the sphere of public space was inevitably subject to this process, both in the physical dimension and discursively, in which a kind of process is observed “occupation” by the state of “humanitarian and cultural public space”9. From all that has been written, a logical conclusion suggests itself that these two concepts — “civil society” / “public space” appear before us as directly related to each other.

Let us now move on from the theoretical and conceptual part to the idea of how the space of Russian cities acquires the characteristics and properties of public space, appearing before us as a platform for confrontation between civil society and the authorities, in the context of the concept of “right to the city”10 mentioned at the very beginning of our article.

One of the main attributes of the city is the central square. The squares of Russian cities, whose architecture was inherited from the Soviet era, are urban spaces well suited for military parades and demonstrations, while alienated and lifeless in terms of interpersonal interaction. A typical urban space of the Soviet era was characterized by monumental architecture, designed to emphasize the ideology of the might of the Soviet government. All this largely determined the symbolic dimension of the Soviet public space, in the scenery of which “the broad masses of the people turned into extremely disciplined citizens.” Thus, space itself in Soviet cities is best interpreted in terms of the control of the state apparatus over the individual: extensive political control and oversight turned “space for everyone” into “space for nobody.”

In the Soviet city, public space is deprived of its main function — creating and maintaining conditions for free dialogue and discussion of the problems of citizens, this function, excluded from the attributes and characteristics of public space, is eventually automatically transferred to the private sphere, the sphere of private life. “Uncontrolled gatherings of people in central open urban spaces were undesirable, and the daily interactions of urban residents were driven into a private sphere or empty no-man’s places: kitchens, garages, backyards and vacant lots, creating in these zones an alternative life imposed on them by the state.”11 The city was deurbanized, and the society was atomized. It was the Soviet heritage and the past of Russian cities that largely determined the functionality of the tools available to civil society, both for the interaction of the city dweller and the space, as well as the citizen and the authorities in a much broader context of upholding the “right to the city”. The authoritarian government is sometimes simply unable to understand the value that public space represents for the townspeople, and the townspeople, whose socialization and formation took place in the conditions of Soviet detachment and the rupture of social ties (social anomie) of the post-Soviet period, do not always find strength and social resources, necessary to assert their rights.

Ideas about public spaces and their impact on civic protests lead to the search for fundamental characteristics to describe this type of space12. The phenomenon of “street protest” is on the agenda, which is inherent in big cities, while the venues for the actions are chosen, as a rule, mainly central or other city squares. If you ask a simple question: “Why do people try to gather in the squares to express civic and political activity?” — the answer seems logical and just as simple: “Because it makes it possible for a large number of people to gather in one place.” Concerning the urban space, the public protest of dissatisfied citizens can refer to the entire set of socially significant problems, for example, to a cultural problem, more precisely, to the ownership and openness of cultural objects and the usual symbols of the city, accessibility to all its inhabitants.

An example of such a protest of the townspeople about a cultural issue can be an episode from the life of the “cultural capital of Russia” St. Petersburg, associated with one of its main attractions — St. Isaac’s Cathedral. The reason for the future civil protest was the message of the governor of St. Petersburg Georgy Poltavchenko that “the issue with the cathedral has been resolved”, i.e. St. Isaac’s Cathedral will be transferred to the use and maintenance of the Russian Orthodox Church. This unilateral “resolution of the issue” caused a wide public outcry and in the shortest possible time grew into an organized form of civil protest. The subsequent politicization of the protest of the townspeople was a response to the attempt at a political solution to the cultural issue by the governor of the city. The further development of the protest was on the rise. On January 13, 2018, first near the cathedral, and then in the square opposite it, a crowd of protesters gathered against the decision of the St. Petersburg governor Poltavchenko. And on December 30, the public was informed that the order on the procedure for transferring St. Isaac’s Cathedral to the use of the Russian Orthodox Church for 49 years, which was provided by the local authorities on December 30, 2016, had lost its force. The agreement with the Russian Orthodox Church was supposed to be concluded within two years from the moment the order was issued, but the spiritual department has not yet sent an official application. On March 29, 2019, information was published that “the issue of the transfer of St. Isaac’s Cathedral to the ROC-MP is no longer on the agenda”, summing up a successful outcome under the protest of St. Petersburg residents.

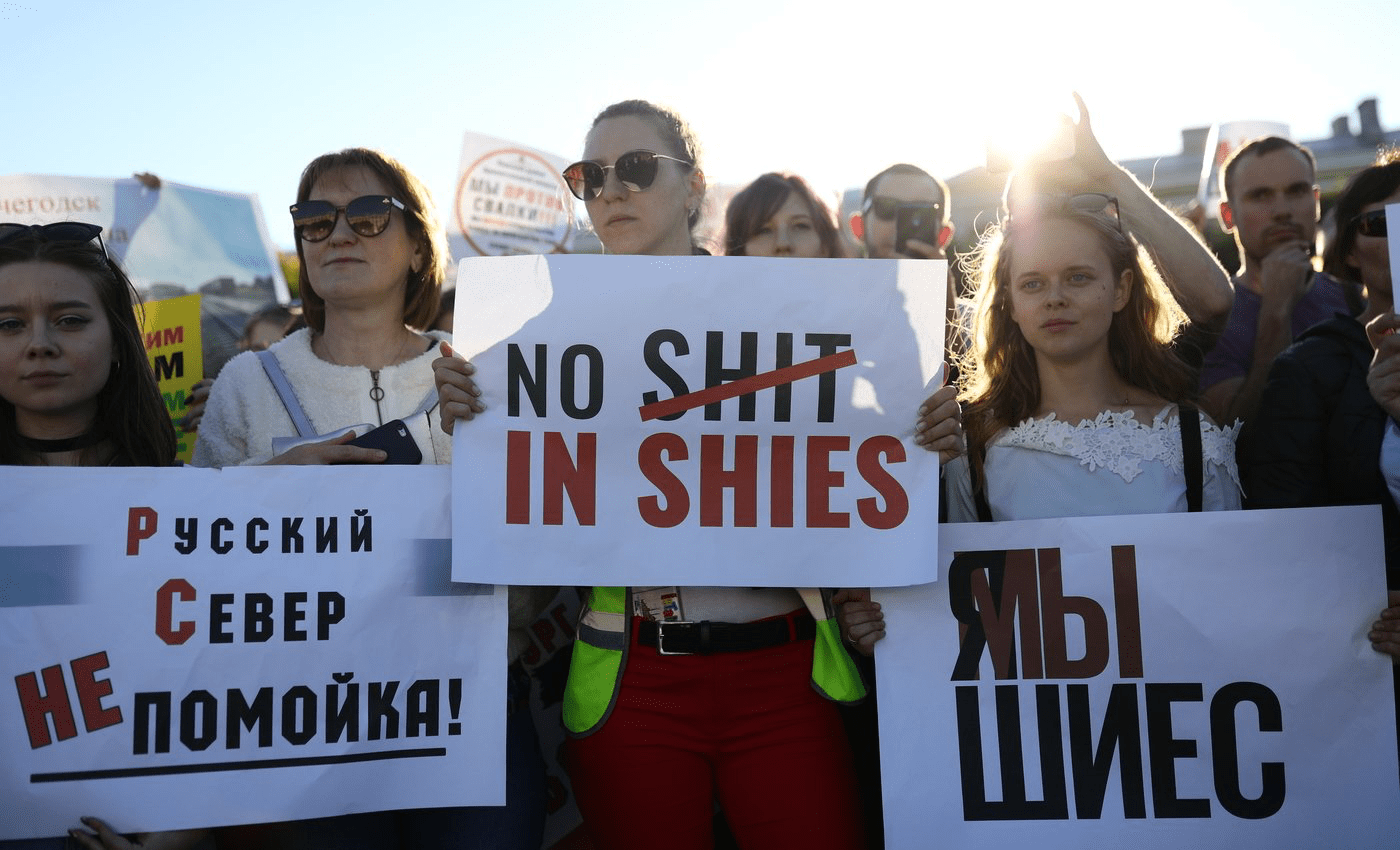

Let us now consider the case of the struggle for the “right to nature” — a protest against plans to build a landfill for the disposal of Moscow’s garbage in Shies in the Arkhangelsk region. Shiyes itself is a small railway station lying on a section of the Northern Railway, this settlement is part of the Urdoma urban settlement of the Lensky district of the Arkhangelsk region. The station gained its all-Russian fame in 2018, in connection with plans to build a landfill next to it, which provoked a massive civil environmental protest. The prehistory of the issue developed as follows. By closing landfills in some cases and forcibly suppressing mass demonstrations in others, by the end of the summer of 2018, the authorities as a whole managed to bring down the wave of Moscow “garbage” protests. Nevertheless, the proposed alternative solution to the problem, namely the removal of Moscow waste to the Arkhangelsk region and the construction of a huge landfill near the Shies railway station, in turn, caused unprecedented resistance by its strength, organization, duration, as well as the public outcry that it subsequently received the support of the local population and the eco-activists from all regions of the country who joined them13. In June 2018, the tent camp of the Shies defenders was opened, in which, constantly changing, lived not only residents of nearby villages and cities of the Arkhangelsk region, but also visitors from Komi, on the border with which the construction of the landfill was planned, as well as the Vologda and Kirov regions, St. Petersburg and other regions.

The resilience and perseverance shown by the protesters in Shies are mainly because people came out to defend their land and their right to live on this land as they want it, and not as they are told, by analogy with the “right to the city”, defending their own “right to nature”. Attention is drawn to the scale and range of problems exposed by the protest, the protesters defended: the social, economic, and cultural basis of their life: the construction of the landfill destroys the forest, and consequently, mushrooms, berries, and other “gifts of the forest”, which can be quite a significant part of the diet in a fairly poor region of the Russian North. In addition, if the landfill construction project is implemented, the Moscow waste buried in the ground will poison the swamps and the local rivers flowing from them for decades, which feed the numerous tributaries of the Northern Dvina river, and hence the fish living in it, which is also a part in the diet of Pomorye residents. In Shies, a local protest, among other things, solved a global environmental problem. According to studies, all pollution from the landfill can enter the White Sea through the northern rivers, and from there directly into the oceans14. In the example of the success of the Shies case, we can see how a productive symbiosis of traditional and modernist social practices of interaction during the protest, which, in addition to the traditional basis of self-organization to protect the usual way of life and the “right to nature” from the alien “Varangians” and local “predators” (Moscow waste business and officials of the regional administration), modern practices of civil society are also being implemented, which are based on horizontal and network connections, on solidarity and trust, leading to the achievement of the set goal. It was also important that the “rear” of the protest all this time was public opinion, which was unambiguously opposed to the construction of a landfill15.

It should be noted that the authorities, for their part, did everything to prevent such a successful completion of the protest, since its success undermined the myth that it is not in the rules of the current Russian authorities to deviate from their plans and goals under pressure from the “street”. All means were used, up to outright deception. That is why the head of the Arkhangelsk region, Igor Orlov, having concluded a behind-the-scenes agreement with Moscow on the import of garbage into the region, at the same time asserts under television cameras that there will be no import of garbage into the region, and then publicly calls “sluts” those who are indignant at his lie. However, as you know, the protest ended in the victory of the activists and the resignation of the heads of two regions at once — the Arkhangelsk region and the Komi Republic. As a result, on January 9, 2021, the Clean Urdoma movement announced the end of the protest, “due to the successful outcome of the people’s struggle against the construction of a waste landfill.” In fact, the landfill construction project was frozen back in 2019, but eco-activists decided to make a final statement only in January 2021, when they finally believed that there would be no landfill in Shies16.

What can the experience of successful civic protest teach us? First of all, behind every success is the painstaking and well-coordinated, albeit not always noticeable, work of public organizations whose activities are aimed at educating citizens about their rights, whether it be the right to cultural heritage or the right to a healthy and clean living environment. In addition, behind the success is the dedication of civil activists who do not stop in the face of any difficulties and even threats of persecution, as well as a special type of protest organization — a horizontal or network structure17. Attention to the problem by independent media is also an important condition for success. Thus, the key to a successful protest is a combination of all these factors. What did it say and what did this protest embody? The protest against the transfer of St. Isaac’s Cathedral to the ROC MP and the protest against the construction of a landfill at Shies station is a “revolution of dignity” at the local level. The protest was provoked not by poverty and low incomes, but by the infringement of the very dignity of people, the disregard for their opinion when solving socially significant issues, precisely such issues that affect the very foundations of people’s lives. “The protest in Shies is not a protest of the lumpen, but a protest of the middle class: by Russian standards, of course, employees of Gazprom and state employees from Urdoma. They have enough money to think not only about finding food but also about comfortable living conditions, which stretches for tens of kilometers into the taiga, where people love to pick mushrooms, fish, and hunt,” says the director of the 7×7 Horizontal Russia portal Pavel Andreev18. In the capital St. Petersburg and Shiyes, a small railway station in the Arkhangelsk region, there was a revival of the understanding that public space exists and must be protected. In Shies, there was a civil war between society and the authoritarian Putin regime, where the state machine was presented in various forms — from the Moscow mayor’s office, which once decided to place Moscow garbage in the Arkhangelsk region, to the highest authorities, which agreed with this, a business that picked up this idea and began to use the funds allocated for its implementation, to ordinary employees of a private security company who beat eco-activists protesting against landfill plans. The garbage problem in the modern world is one of the most important social, technogenic, and, ultimately, political problems, involvement in the solution of which contributes to the awakening of the civil consciousness of society19.

At the same time, of course, this is an “unfinished revolution of dignity”. Having achieved local success, civil society in Russia has not been able to extrapolate this success across the country. And the inability shown in the issue of building long-term ties20, ultimately, led to a global defeat of civil society, its collision with a skating rink of repression, as soon as the Russian dictatorship once again raised the stakes, shifting arrows from an internal enemy to an external one, in a full-scale war with Ukraine. Later, the protest in Khabarovsk, political in its agenda, as localized as the environmental protest in the Arkhangelsk region, would again repeat the mistakes that, alas, the Russian protest repeats over and over again21.

The history of local victories of civil protest in Russia is, at the same time, a history against the background of a global defeat, without attention to which, however, we will inevitably be threatened with repeating most of the unlearned lessons in practice, and this is less preferable than repeating in theory.

______________________________

1. Arendt H. Vita Activa, or About an active life / V. V. Bibikhina. M.: Ad Marginem Press, 2017 // The space of the public and the sphere of the private. pp. 35-99.

2. Habermas. Theory of communicative action / translation from German by A. K. Sudakova. M.: Publishing house Ves Mir, 2022.

3. Jürgen Habermas developed the conceptual idea of “publicity” (Öffentlichkeit), which incorporates a number of concepts. Such concepts as “public space”, “public sphere”, “publicity” in Habermas’s theory appear as a virtual media space in which public opinion is formed in the course of active and evaluative-critical debatable communicative activity (On the concepts of “publicity”, “public opinion” (public opinion), “public spirit” in the context of the history of German bourgeois society, as well as German classical philosophy (Kant, Hegel, Marx) and the theory of classical liberalism (Mille, Tocqueville), see: Habermas. Structural change in the public sphere / translated from German by V. V. Ivanova, edited by M. M. Belyaev).

4. According to the sociologist Lev Gudkov: “A sign of serious changes, speaking of civil society, would be systematic, everyday party or public communication work to represent group interests and consolidate society,” but at the same time, in relation to Russian society, according to the sociologist, “we we are dealing with sporadically occurring reactions to events that disturb people, which in turn can be considered as a manifestation of accumulated diffuse irritation, dissatisfaction with the system” (Gudkov L. Protests become routine and become part of the system // Moscow protests and regional elections / ed. K. Rogova. M.: “Liberal Mission – Expertise”, 2019. P. 103-104).

5. Vorozheikina T. What Happened to Russian Society in Putin’s Twentieth Anniversary? / The article was published in the journal “Inviolable Reserve”, issue No. 129 // Access on the website of the “New Literary Review”: https://www.nlobooks.ru/magazines/neprikosnovennyy_zapas/129_nz_1_2020/article/21948.

6. Among such organizations, one can name the Anti-Corruption Foundation of Alexei Navalny, known for exposing the facts of corrupt activities by representatives of the Russian political (and associated business) elite, FBK website: https://fbk.info. As well as the network society of scientists and experts Dissernet, whose tasks include the implementation of an independent examination of kandidat and doctoral dissertations defended in Russian scientific / educational institutions, and in the widest possible disclosure of the results of such examinations, the website of the network society Dissernet: https://www.dissernet.org.

7. An example here is the activities of volunteer and charitable organizations, their first persons are well-known media personalities, and the means to carry out the work are direct or indirect financial assistance from the state. For example, the Podari Zhizn charitable foundation, whose founders include the popular Russian theater and film actress Ch. Khamatova, website: https://podari-zhizn.ru.

8. We also considered the problem of the “conservative turn” of the Russian government in our other article: Rudkovsky S. The problem of institutionalization of Russian political emigration in the context of the Russian war in Ukraine // Article on the website of the Free Russia Institute: https://freerussiainstitute.org/publications-ru/institualizacija-rossijskoj-politicheskoj-jemigracii-v-kontekste-vojny-rossii-v-ukraine.

9. The process of “occupation” by the state of the cultural sphere can be observed in the example of the memorial action “Immortal Regiment”. Initially, this action was initiated in 2012 by journalists from the Tomsk independent television channel TV-2, but then the action came under close attention from the state, and soon it naturally turned into the appropriation of its meaning and goals by the so-called. to the all-Russian civil-patriotic movement “The Immortal Regiment of Russia”, with which it is now associated throughout the world, presenting itself in a vulgar-patriotic form, far from its original one: instead of portraits of real relatives of the participants in the action, veterans of the Second World War, there were photographs of Soviet statesmen (Stalin, Molotov, etc.), red banners and flags and Soviet symbols became an obligatory attribute of the action. Currently, students of schools, technical schools and universities, officials of various levels, as well as public sector employees are attracted to participate in the action on a voluntary basis. // The discourse of the Second World War has long acquired the status of an important element of the historical policy of the Putin regime; this role has increased especially noticeably after the start of the Russian war in Ukraine.

10. The “right to the city” is a concept first formulated by the French sociologist Henri Lefebvre in his book of the same name (French “Le Droit à la ville”). The basis of the concept is “the demand for a renewed, expanded right to access urban life.”

11. Cited from: Zhelnina A. “Tusovka”, creativity and the right to the city: the urban public space of Russia before and after the protest wave of 2011-2012. / The article was first published in the journal Stasis No. 2, 2014. P. 269.

12. Particular attention in this regard deserves the work of Sharon Zukin, an American professor of sociology and an expert in the field of urban studies, in which a triad of criteria for “public space” is formulated: 1) these spaces are characterized by public administration; 2) they are equally free for everyone without exception; 3) the interests of people in these spaces are aimed at achieving public, and not individual or private goals (see Zukin Sh. The Naked City. Death and Life of Authentic Urban Spaces / translated from English by A. Lazarev and N. Edelman, under scientific V. Danilov, ed., Moscow: Gaidar Institute Publishing House, 2019, pp. 195-197).

13. Local independent environmental organizations very soon became involved in the protest, both those that already had some experience in upholding the environmental rights of citizens, and those that were formed ad hoc, directly during the protest in Shiyes. Among them are the movements Clean Urdoma, Committee for the Protection of Vychegda, Stop Shiyes and many other environmental movements of the Arkhangelsk region. For example, the Arkhangelsk environmental movement “42” (named after Article 42 of the Russian Constitution, which guarantees every Russian citizen the right to a favorable environment and the right to receive reliable information about its condition), whose merits, just the other day, namely 12/9/2022, once again noted by the Russian authorities, having included the public organization in the “register of foreign agents”. Website of the ecological movement “42”: https://eco42.org.

14. Ochkina A. How the Russians protest. Results of monitoring protest activity in the second quarter of 2019: Report // Center for Social and Labor Rights, 2019.

15. On August 26, 2019, the Levada Center, an independent center for sociological surveys, published the data of a survey conducted in which residents of the Arkhangelsk region took part. According to the results of the survey, 95% of respondents were against the construction of a landfill in Shiyes, and only 3% agreed: https://www.levada.ru/2019/08/26/otnoshenie-zhitelej-arhangelskoj-oblasti-k-proektu-stroitelstva-ekotehnoparka-shies.

16. In December 2021, a crowdfunding project was launched to raise funds for the publication of a book about the Shiyes protest, the fundraising for which is still ongoing. According to the plan, it will include more than 100 photographs of nine authors and memories of people who took part in the activities of the environmental camp. More information about this project can be found by clicking on this link: https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2021/12/07/nu-ka-tikho-ustroili-tut-shies.

17. This is especially evident in the example of the Shiyes protest. There were no leaders in the movement, each district had its own group of activists — for example, Clean Urdoma or the Vychegda Defense Committee, which did not depend directly on other groups, but at the same time coordinated its actions with them. In each initiative group there is a constant rotation of its members. “An attempt to split the movement is impossible, since the masses of the people do not have a single system of organization,” say activists of the public campaign “Pomorie is not a garbage dump.” Despite provocations by the authorities, unpunished beatings of activists by employees of private security companies, accusations of protesters of illegal actions and insults they received from the police, the participants in the Shiyes protest were fully aware that, while preventing an environmental catastrophe, they were simultaneously defending their own civic and human dignity, one’s pride, thus an ecological protest, at the same time became a moral protest, acquiring the features of a real “revolution of dignity”.

18. Quoted from: “Shiyes syndrome. How the activists announced they had won the epic war against the Shiyes landfill, and why they all quarreled immediately afterward”, https://meduza.io/feature/2021/01/20/shiesskiy-sindrom.

19. As you can see, the “garbage problem” is a problem not only for Russia, but also for European countries, the solution of which can bring impressive political dividends. The current president of Slovakia, Zuzana Čaputova, gained popularity and fame during her time as a lawyer for activists who protested against a garbage dump, successfully defending the right of citizens to a healthy environment. After that, she won the presidential election, becoming the head of state.

20. You can read more about the complex history of relations between eco-activists and the inability to come to a long-term basis for interaction, using the example of the protest in Shiyes, in the report of Andrey Pertsev, a special correspondent for Meduza: https://meduza.io/feature/2021/01/20/shiesskiy-sindrom.

21. Materials on the Khabarovsk protest 2020-21 on the DW website: https://www.dw.com/ru/habarovsk-protesty-furgal.