On February 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin, in his euphemistic manner, announced the invasion of Ukraine — a sovereign state — and outlined loud, unsubstantiated “aspirations”, among which are “demilitarization and denazification of Ukraine”, “bringing to justice those who committed numerous bloody crimes against civilians.” He also mentioned that “our plans do not include the occupation of Ukrainian territories.” The past eight months have given rise to many questions, and the fundamental “aspirations” have completely disappeared from the political agenda. What are the contradictions in the Kremlin reality and what can this lead to?

State-owned and therefore controlled (and hence propagandistic) media channels, supervised by Alexei Gromov, the first deputy head of the Presidential Administration, play the key role in the dissemination of the Kremlin’s “picture of the world.” They broadcast events in the manner prescribed by the authorities and beneficial to the authorities, they are deprived of independent and impartial analysis, independent interpretation of what is happening and independence as such. The scale of their activities is evidenced by what they are doing — designing a deliberately biased political reality according to instructions, or rather manuals.1,2

This “reality” is often taken for granted, as the only true representation of events. Being saturated with ideologemes, substitution of concepts (clapping instead of explosions, hitting a house instead of crashing, etc.) and an uncontested interpretation of events, this “reality” may seem unshakable and indestructible to a wide audience. Wide, but not total. Unfortunately, it is not possible to obtain reliable data due to the lack of conditions for objective sociological surveys in Russia, however, it is obvious that there is no dialogue between the two sides — opponents of the war in Ukraine and those supporting the “special military operation”. There are rather more disputes and showdowns, leading to what Andrei Loshak’s film “Break in Communication” tells about.

However, the longer Russian aggression in Ukraine continues, the more fragile the Kremlin’s “indestructible reality” becomes, the “seams” (and sometimes even “holes”) of which are exposed with each new controversial decision, whether military or political, by the ruling elites. What changes did the Kremlin’s “picture of the world” undergo during the war? How do these changes contradict (and do they) contradict each other? And why are they able to “wake up” Russian society?

The nature of social and political reality

The construction of reality is the center of interweaving of many disciplines — philosophy, history, media, psychology, political science, etc. Due to such interdisciplinarity in the issue of creating reality, or a picture of the world, there are quite a lot of gray areas that are often exploited by interested parties and are firmly planted in the logic of ordinary citizens (I haven’t seen it — I don’t believe it, no one knows the truth, everyone has their own truth, and so on). Unfortunately, at the moment there is no single, accepted by all areas of scientific research apparatus of approaches for studying the nature of reality, which could not only reflect the process of creating this reality in a structured and organized way, but also highlight the aspects and trends of its assimilation by the target audience.

Despite this, there are established and accepted theories in the media context about what reality is (from MediaMaking: Mass Media in a Popular Culture, 2006, pp. 200-201):

Firstly, reality is perceived as a certain set of material facts — what a person sees, hears, perceives, and is also able to explain and express using language, being understood by others. All this is largely determined by culture, a kind of code, a predetermined place of birth, environment, upbringing and other circumstances.

Secondly, the question of reality is revealed in Plato’s allegory about the cave. Chained and deprived of light, the prisoners perceive any reflections on the wall as reality, although, in fact, what they perceive is an illusion (of which they are unaware). This reveals the idea that our sensory world (the external world) is an illusion behind which reality itself is hidden. However, in order to understand reality, it is necessary to know about the cause-and-effect relationships between the sensory world and underlying reality. Without this knowledge, only an illusion remains.

The third concept of reality considers reality solely as a human invention that can be created, destroyed and recreated again. In this approach, reality must be created to carry meaning (understandable to the target audience).

It is the third theory that is the object of close attention and in-depth study in the media field, since it is media channels that broadcast social and political realities through the representation of source materials.

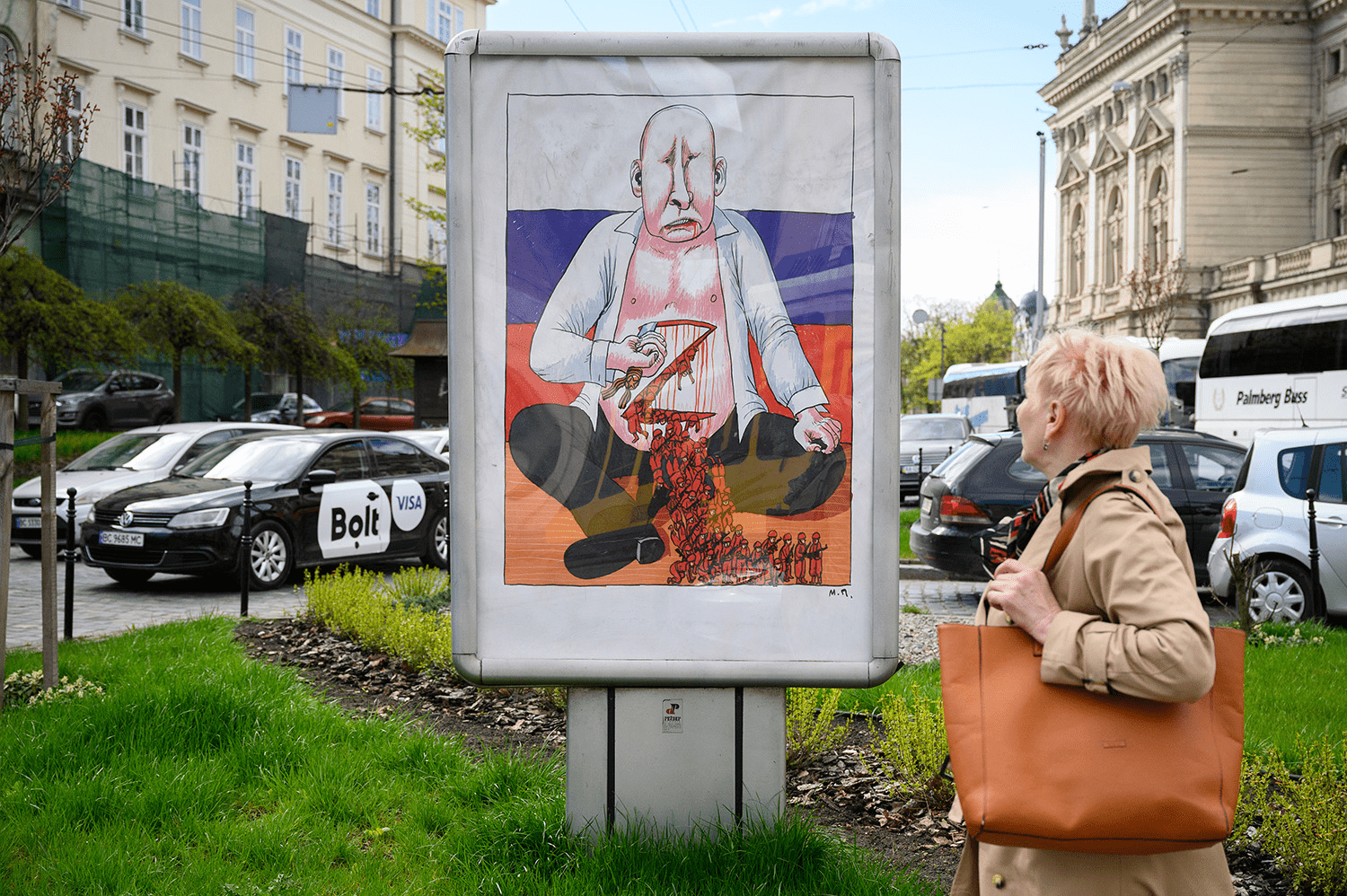

Naturally, when the entire media apparatus functions as a uniformly tuned transmitter of information, then there can be no talk of other realities. In this case, the parallel between the prisoners of the Platonic myth, chained to the wall and deprived of light, and the general audience, chained to the TV and deprived of an alternative (due to the lack of critical thinking, fact-checking skills, difficult access to information and other reasons), looks extremely appropriate.

At the same time, the Kremlin’s “world of shadows” is far from its inviolability. It is very fragile in the sense that it carries a lot of fundamental and structural contradictions, which propagandists are trying to hide so desperately and persistently, meekly following the received manuals. What exactly are we talking about?

What is wrong with the “Kremlin world”?

Political documents, speeches and interviews of Russia’s power elites, including the current president of the Russian Federation, have already become part of history, which is quite amenable to real-time analysis.

Let’s start with the key “aspirations” mentioned by Putin in his speech of February 24, among which are such concepts that have scattered through all state media channels, such as the “demilitarization” and “denazification” of Ukraine. It only took a few months for the new “aspirations” to start spreading. However, the paradox lies in the fact that the so-called “demilitarization” of Ukraine only led to the strengthening of its defensive potential and the application to join the NATO alliance. Besides, the result of Russian aggression was the accession of the previously neutral states of Sweden and Finland to the NATO alliance.

As for “denazification”, the term is no longer in the active vocabulary of either the highest political strata or propagandists. Moreover, the articles published on BBC News Russian Service and Meduza, with stories of combatants on the side of the Russian troops, tell about the rethinking of what is happening, including in relation to the “denazification” of Ukraine.

As events unfolded, the media focus of the state media, especially in the days when “denazification” was losing relevance (due to the groundlessness of such an accusation and the lack of substantive evidence), shifted to the internal struggle against “national traitors”. Their list turned out to be impressive, starting, it would seem, with the ones most distant from politics — national pop-stars. The narrative of the “economic struggle” unleashed by the West against Russia in response to the “special military operation” became a step of further escalation. The “economic struggle” soon gave way to an “economic war” against Russia, and after that the media agenda reached the scale of confrontation with the collective West, which unleashed a war in Ukraine, according to Putin. Note that Putin devoted more than half of his address on February 24 to this!

If we analyze his first mention of Ukraine, then we will find it not even in the middle of the speech, but a little lower! That is, on the day of the invasion of Ukraine, Putin devoted an unkind half of his speech not to explaining the aggression against Ukraine, but to historical discourse and confrontation with the West. Compare: the word “Ukraine” and its derivatives are used 19 times in the text, “NATO” — 9 (+ twice “North Atlantic Alliance”), “USA” — 11 (+ once — “American”), “West” and its derivatives — 8. Was the speech really about the invasion of Ukraine?

Among other blunders of the Kremlin reality are biological laboratories, which, according to the Russian side, were intended for the distribution of biological weapons on Russian territory. The story had a short-lived effect, caused a wave of indignation on the part of experts, and the evidence that was “collected” by the Russian side remained with it. Eight months later, parallels from the same field appeared: first, the Russian side began to actively spread the version about the impending use of a “dirty bomb” by the Ukrainian army, and after that, Vasily Nebenzya, Russia’s Permanent Representative to the UN, delivered his speech dedicated to “combat mosquitoes”. The main argument of the politician was that a patent was issued in the United States for the distribution of infected mosquitoes using drones. However, no confirmation of the existence of such a government program in the United States by Vasily Nebenzya followed. By the way, the patent was indeed issued, which gives the story a certain comical character, given what other patents issued to the inventor of the drone with “combat mosquitoes” (for more details, see the analysis article at “Provereno.Media”).

Russian officials has already spoken several times, as colleagues from Meduza noted, about “gestures of goodwill.” There have already been three similar “gestures of goodwill”, and one of them was presented to its own citizens (after the announcement of “partial mobilization”). The first was associated with military clashes around Kyiv and Chernihiv, which ended with the retreat of Russian troops, but were presented to the audience as a withdrawal of the RF Armed Forces “to create favorable conditions for negotiations.”

Another withdrawal of the Russian army, presented as a “maneuver”, concerns the retreat from the previously annexed Kherson. The Kremlin’s official media initially followed the official interpretations of the surrender of the city (the RF Armed Forces think “about the life of every Russian military”), and after the “regrouping” of the Russian armed forces and the return of Kherson by Ukraine, they began to spread news about the Ukrainian filtration camps, while not showing any enthusiasm in covering the filtration camps for Ukrainians in Russia, as well as the fate of the Russian military who refused to fight.

Another of the most obvious cracks in the “Kremlin reality”, which Putin spoke about in the same address, lies in the annexation of Ukrainian territories. Although the speech itself contains the statement that “our plans do not include the occupation of Ukrainian territories” and that “we are not going to impose anything on anyone by force”, objective facts testify to the contrary: the Russian Armed Forces first invaded the territory of Ukraine, and then hastily annexed part of its lands in the fall.

These inconsistencies are so significant and fundamental that they can hardly be explained by changes in the development of hostilities. In addition, the phrase: “All the tasks of the special operation <<…>> will be completed” has disappeared from active use in the rhetoric of the upper strata. This could imply the fact that the Kremlin does not quite understand what is a task and what is an “aspiration”. Putin himself undertook to clarify the situation in his Valdai speech, once again reminding the audience why Russia invaded Ukraine: “I initially said that the most important thing is to help Donbas. If we had acted differently, we would not have been able to place our armed forces on both sides around the Donbas.” “Help Donbas”? But what about “demilitarization”? “Denazification”?

Why is Kremlin reality doomed?

In addition to very clear and understandable reasons, such as the inevitable fall of any dictatorship, there are scientifically oriented processes inherent in any society immersed in the high-tech world of the 21st century. Thus, the social psychologist Arie Kruglyansky coined the term “cognitive closure” — the human desire to obtain a convincing answer to a question with an obvious aversion to any manifestation of uncertainty.

It is widely known that the Kremlin’s one-sided “picture of the world” has been broadcast to the Russian audience for at least a decade. It “settled” in the addressee and became a very common worldview. Another question: does it still exist? Will it stay?

According to Kruglyansky, there is a way out of the seemingly vicious circle of information (propaganda in Russia): a person begins to question, think and think carefully when some external risk appears, for example, punishment (criminal article). And the stricter it is, the more balanced, accurate and cautious people become in their judgments, thereby increasing the level of their criticality and deliberation of their decisions. Thus, in a sense, in contrarium, the Kremlin, with its repressive decisions, gives more and more reasons to think even to those who were not ready to question what was happening before. Even the recent active participation in the global world does not play into the hands of the ruling elite: the process of “isolation” from the outside world affects both the economy of the state and the standard of living of citizens — obviously, it is not getting better. For the same reason, it is difficult to imagine Russia as a model of the current DPRK — people have something to compare with, and people already now feel what it is like to be cut off from advanced technologies, international banking systems, and so on. At the same time, we cannot expect that the overnight emergence of a question in the minds of Russian citizens will induce them to actively participate in the life of the state (largely due to the theory of the spiral of silence). And yet, a lot of things begin precisely with a question — from the story of Parzival:

A question! It was worth asking you

Just one question, and everything

Would change dramatically in a minute!

In addition to the Kremlin’s repressive approach towards Russian society, the Kremlin’s thrashings and contradictions, as well as attempts to patch up holes in its reality, expose its fragility and failure already now, not to mention the long term, and at the same time create the ground for the growth of consciously dissatisfied. The stronger and more obvious the internal dissonance among Russian citizens is expressed, the more actively they will reject the picture of the world imposed on them, which does not promise a bright future and prosperity. This future is already in the fog, and the consequences of the decisions of the ruling elites are returning to their native corners of the country with “load 200”, wounded and crippled lives.

The further — the closer the end of the Kremlin’s “truth”. That short-lived “world of shadows”, which is gradually being destroyed by the minds of its creators.

______________________________

1. According to two leading political communicators, Sidney Kraus and Dennis Davis, “Political reality is shaped by mass communication reports that are discussed, reshaped, and interpreted by the citizens of society. The universality of this process is the reality” (from The effects of mass communication on political behavior, 1976, p. 211).

2. What Dan Nimmo and James Combs put into the term mediated political reality, where “political reality” is the product of a multi-level and multi-directional process, and not the product of direct participation: our perceptions are shaped by focused, filtered, fantasized perceptions of a number of mediators (from Mediated Political Realities, 1983, p. 2).

3. The reality in which people live is conditioned by ideology. It determines how a person understands this “world”, how he interacts with it, what he takes for granted, what is common sense, and so on (from MediaMaking: Mass Media in a Popular Culture, 2006, p. 206).