Over the past three years, the Russian authorities have been intensively creating a submissive and humble, comfortable information field for themselves, persecuting whistleblower journalists and their lawyers. And if the case of Ivan Golunov was remembered as a triumph of public outcry, then in the future the situation changed dramatically for the worse: a 9-year term for anti-corruption investigator Alexei Navalny, a 15-year sentence for publicist and head of the Karelian branch of Memorial Yuri Dmitriev, a 22-year sentence for journalist Ivan Safronov, the forced liquidation of the Open Russia movement, a 4-year suspended sentence for human rights activist Anastasia Shevchenko, the closure of Memorial and Astrea — the list, alas, is much more impressive than the few examples mentioned above. In 2021 alone, more than 100 individuals were recognized as “foreign agents” in Russia, and the number of political prisoners exceeded 1,000. Naturally, fear of reprisals reigns in the country, but, by the way, even this does not stop journalists and human rights activists loyal to their cause. What do they have to face in trying to establish justice?

The relationship between authorities and journalism is a critical aspect of understanding the state regime. It sheds light not only on the political system but also on the culture of the environment, and its social life. Meanwhile, in modern Russia, journalism often found itself drawn into intra-elite conflicts, which mainly boiled down to a struggle for power and the preservation or redistribution of it.

Authority — any authority — has always had and always will have leverage. A classic example from the history of journalism is the fate of one of Benjamin Harris’ newspapers in 1690. The publisher, who left England due to government repression, in the first and only issue of “Publick Occurrences both Foreign and Domestick” touched on the taboo issue of the condition of the Native Americans. Harris was soon stripped of both his newspapers and his freedom by the state’s governor, and media licensing became an important bureaucratic procedure that provided the authorities with the opportunity for some filtering.

Formally guaranteed by the Constitution of the Russian Federation, the freedom of the press remains a “subject to” — for example, under martial law. In addition, journalists (and with them both human rights defenders and researchers), publishing this or that information, even if obtained from open sources or officials, risk being prosecuted for disclosing state secrets, treason, or espionage in favor of enemies — very effective tools of influence (due to very vague wording). The last 3 years of the practice of Russian justice are eloquent proof of this.

Right to judge

In Russia, the persecution of journalists was not an extraordinary event until 2022. The case of Ivan Golunov was indicative in many ways. The journalist was detained in the summer of 2019 on suspicion of selling drugs. Drugs were indeed found on Golunov: they were planted on the journalist by a law enforcement officer, which Golunov himself stated, categorically denying his involvement. It seems that none of the authorities could have imagined what happened next: the flagrant injustice, the fabrication of the case, and the role of the police in the staging provoked large-scale protest campaigns, the scope of which could only surprise the law enforcement authorities. Now it is hard to imagine, but within a few days, the Ministry of Internal Affairs stopped the criminal investigation and fired five policemen who took part in the arrest (only one of them admitted his guilt).

Of course, the resulting public outcry played a role against the lawlessness concerning Ivan Golunov. And not only that. The scope of the public campaign demonstrated the willingness of people to fight for truth and justice. This could hardly have gone unnoticed in government circles. Over the next two and a half years, the law was “improved” and “finalized” so much that even peacefully standing people became malicious violators of the very order that the police monitor the rights of.

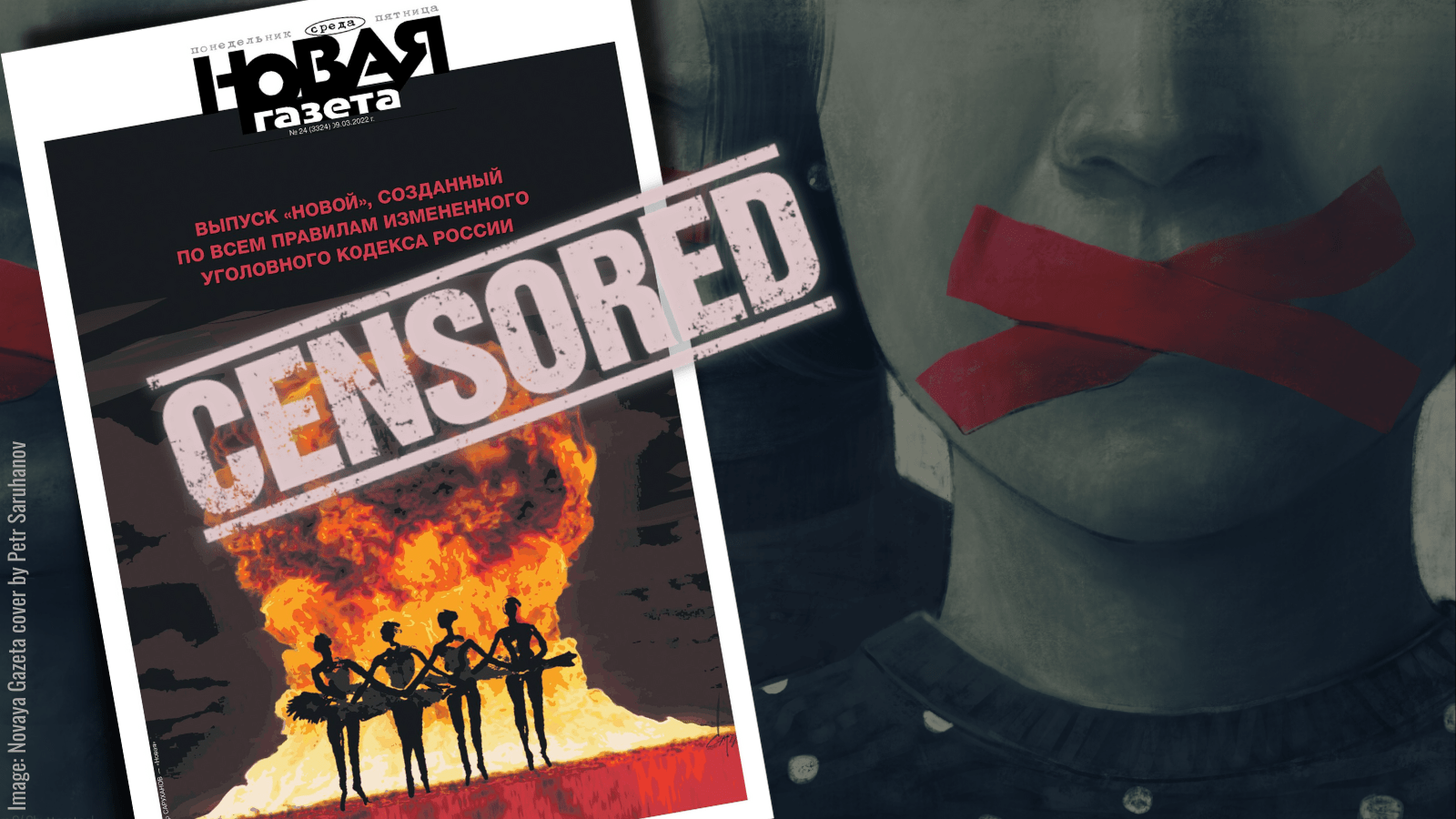

The “evolution” of persecution against journalists in Russia is also indicated by their scale – from personalities to entire media editorial offices. Separately taken journalists continue to “deserve” the attention of the authorities, but the entire editorial offices receive much more of the attention. Thus, the authorities get rid of Novaya Gazeta as if from a witness who caught the murderer at the moment of committing a crime. However, the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation sees purely preventive goals in its actions. In September alone, the licenses of the print and electronic versions of Novaya Gazeta were revoked, and the publication Novaya Rasskaz-Gazeta lost its registration certificate. These are the principles of the current “prevention”.

Revealing materials, folding a whole picture that is not comforting for the authorities from small pieces of available and verified data and facts scattered across offshores, information from the internal government kitchen… The more noticeably the information field boils after publications, the more acute the need to control the uncontrolled. Not to see this after February 24 means deliberately turning away in the other direction.

Currently, the obvious and unjustified use of the legal sphere in the selfish, predatory interests of state power looks like a logical step in the policy that was being built before our eyes, but few were ready to believe it. The state, as a form of organization of society, has an apparatus of control and coercion. It is necessary to exercise management at many levels, including the institution of law or the institution of journalism. However, the concept of “management” in Russian political circles is perceived too literally.

Doubts about the fairness of the domestic judicial system date back to the Soviet era (however, the current government does not take this into account when it calls Russia the successor of the USSR): “Now in the USSR the place of the former Senate is occupied by the Supreme Court. It is the top of the ladder of the Soviet courts; it is the guardian of law and justice (for example, “class”); it is the creator of judicial traditions and the guardian of truth, the speed, and accuracy of all judicial functions. If it is not safe in the “Supreme Court”, what can be demanded from the lower instances subordinate to it! <<…>> In the RSFSR, in the most “hot” cases, where we are talking about living people sentenced to prison, exile, etc., when the Supreme Court itself cancels the sentence pronounced by the lower court and delivers the “immediate release” of the convicted, this “immediate release” is almost always delayed for an “indefinite time” (excerpts from the article “The Judgment is Right and Speedy”, published in the émigré newspaper Latest News on August 22, 1939).

Has the letter of the “law” become clearer or more favorable to people? On the contrary, the very word “court” in Russia has ceased to have any connection with the concepts of justice and honesty. The current “court” resembles a mythical, but sometimes clearly visible Cerberus, faithfully and dutifully sitting on a leash at the Russian authorities. For the most part, the same thing happened to journalism, at least to traditional journalism. The Kremlin media are perceived by an informed audience only as a synonym for propaganda and manipulation of public consciousness.

The only information field in Russia where information from various sources is still possible is the digital environment. Digitalization has helped journalism in Russia stay alive. Moreover, many international hostings are still available inside Russia that do not require VPN applications, and Russian-speaking leaders of free opinions, despite the ongoing Roscom-Nadzor, can be heard through a variety of platforms. For how long? After all, the government of the Russian Federation is actively “working through” the Internet environment, whitewashing its own and denigrating others…

Cleanups on the Internet

In the Internet environment, opposition and independent media publications have become a real challenge for the Russian power elites. Given the speed of distribution of journalistic investigations and their coverage, topics that often went beyond the published ones were exposed, among which were the activities of PMC Wagner and its connection with Yevgeny Prigozhin (only on September, 8 years later, he recognized it), the possessions of the country’s top officials, financial schemes, etc. The professional activities of non-state journalists can, if not break, then definitely undermine the illusions built by the Russian government over the years, give rise to seditious questions about the legitimacy of statements about a “special mission, obvious superiority over the West” and, in general, help to question and reconsider attitudes towards the current government and the picture of the world imposed by it (Medusa’s article about those who were at war and their attitude towards it and mobilization).

It is obvious that the relationship between the authorities and journalism “evolved” along with the consolidation of the Putin regime — from attempts to build a complex system of balancing the “carrot and stick” with the help of manipulative and repressive “taming” and to a brutal landing “on a chain” with the help of primitive administrative resources and repressive legislation. Is it any wonder that “the creation of an additional mechanism for protecting the rights and freedoms of citizens in the digital environment” took place in July 2021 — only a year after the extremely controversial referendum on the Constitution of the Russian Federation and six months before the unjustified invasion of the territory of Ukraine.

The instructions to the law state that “unreliable or discrediting information” can be deleted, bypassing the canons of the judicial order. Applications are considered at the level of the prosecutor’s office, and Roskomnadzor plays the role of an executor. In addition, if the media refuses to remove the information or disagrees with the decision of the prosecutor’s office, the supervisory committee is authorized to restrict “access to information resources that disseminate the specified information.” In other words, block.

And there is nothing new in this: Putin repeatedly spoke about the global network, starting in complimentary tones and gradually moving towards the threats that the network brings with it. One can only add that between Putin’s remarks and the event context of the days when they were uttered, there is a correlation noticeable to the naked eye.

Without the right to protection

At the same time, several years ago, the human rights organization Agora in its report “Russia. Internet Freedom 2016: Under Martial Law” stated clear signs of state Internet censorship. The phrase “under martial law” sounded prophetic, but now it only demonstrates a consistently built government policy of “criminal blackmail” in relation to their citizens (from threats of criminal prosecution against opposition politicians, like Dmitry Gudkov, who was forced to leave Russia, and to the recently adopted laws of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation on discrediting the Russian army and on fakes, as well as tougher criminal penalties during the period of mobilization and wartime).

Meanwhile, Agora was among 73 NGOs that ECHR took the side of, which in mid-June recognized the law on “foreign agents” as violating the right to freedom of assembly and association. However, by that time, the Russian Federation had already adopted its own law on the non-execution of decisions of the ECHR.

Thus, human rights organizations, traditionally defending the rights of political prisoners, journalists, and people who have become victims of unjust persecution, turned out to be among the opponents of the ruling regime. So, for example, two of Ivan Safronov’s lawyers, Ivan Pavlov and Dmitry Talantov, themselves became defendants in criminal cases, the latter even faces up to 15 years in prison. The criticality of the situation in the field of rights is evidenced by a joint report prepared by 10 human rights NGOs, including OVD-Info, Nasiliyu.Net, Memorial Human Rights Center, Civil Control, Public Verdict, Sfera, Legal Initiative, Center for the Protection of Media Rights, the Movement of Conscious Objectors and the International Committee of Indigenous Peoples of Russia. The report provides facts and evidence of politically motivated repressions, an unprecedented level of suppression of rights and freedoms, the impossibility of holding peaceful rallies, and, consequently, the enslavement of civil society, the introduction of military censorship, violence, and persecution.

In September, the UN Human Rights Council condemned the Russian authorities for persecuting war opponents. UN Special Rapporteur Mary Lawlor also condemned the persecution of human rights defenders, expressing concern in her speech about the amendments to the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, which relate to “confidential cooperation” with international organizations and provides for a prison term of up to 8 years. As the specialist noted, there is no reason to believe that the law will not become another weapon for the persecution of human rights defenders and an additional step to “strangle civil society”.

If earlier “suffocation” could only be felt by activists, journalists, opposition politicians, and human rights advocates, that is, by those directly related to the political and public life of the Russian state, then after the start of “partial mobilization”, that same “suffocation” became noticeable the ordinary Russian men and women, each of whom, once in the war, risks paying for it with their own lives. If until September 21 life flourished in the cities of Russia, or created the appearance that it was flourishing, in the usual way, then on the 21st many learned not only about what happened on February 24, but also that the war concerns the Russians and demands their bloodshed.

The repressive methods of the Russian government are no longer an element of intimidation in the fight against unwanted people, but an official way of managing civil society, or rather, its suppression. It is against this that brave and fearless journalists who provide objective information within the Russian Federation, and no less brave and fearless human rights activists who defend the rights and freedoms of civil society and those who find themselves face to face with the repressive letter of the law, rise up.

It is they who defend the right of Russia — free Russia — to the future.