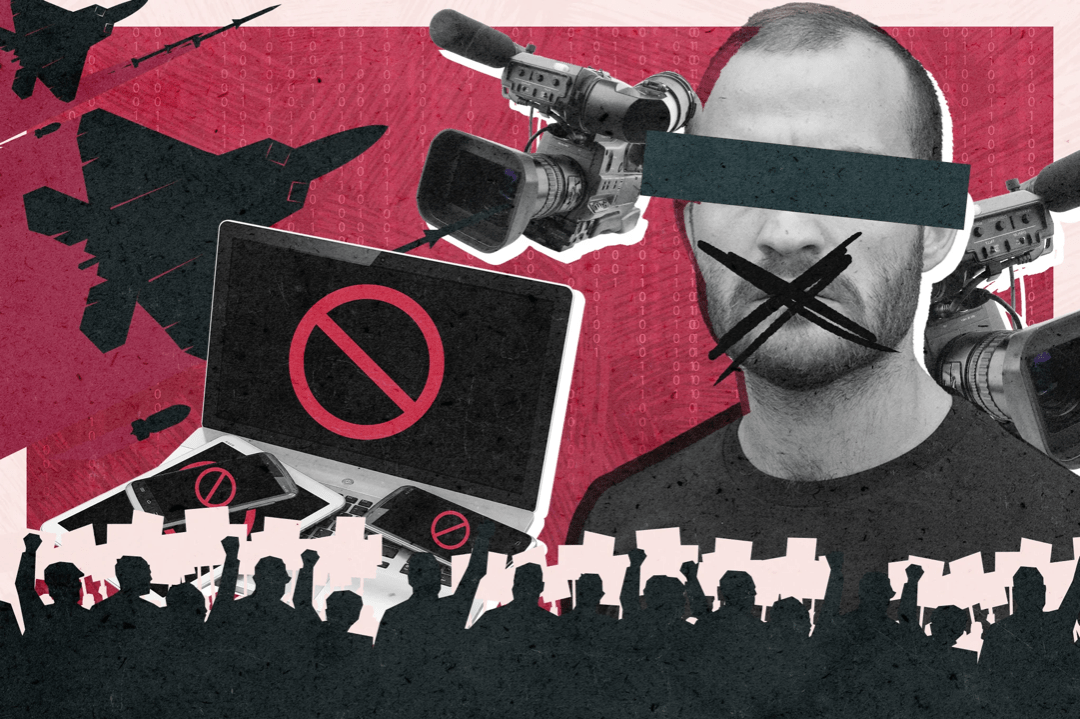

For the past few months, the Russian media space has been the epicenter of the fire, the flames of which broke through on the morning of February 24th. This flame carries too much destructiveness, absorbing human destinies and lives, values , and foundations, among which is the fundamental right – the right to freedom of speech.

Over the past few months, the media in Russia have undergone drastic changes: some organizations closed down, others were closed (or blocked), others remained and continued their work, either “for the good of the state” or for the glory of the timid guérilla journalism. In this article, we will talk about the key and even critical media shifts that have taken place in the journalistic world in Russia, as well as the goals and “achievements” of the military censorship imposed by the Kremlin.

Media turmoil in the first months of 2022

In the already so distant, although not even a century had passed, 1939, an eloquent phrase by then Prime Minister of Estonia, Kaarel Eenpalu appeared on the front page of the Old Narva Listok: “We only know one thing, that no one wants war, but, nevertheless, is preparing for it” (printed edition of August 16, 1939). Then, in August 1939, many indirect factors pointed to the futility of the “negotiating table”, but the media rejected the reality to the last and put off the recognition of the inevitable and inevitable fact – the approach of war.

After 83 years, no matter how the opportunities have changed, the media – traditional and new – again failed to form a single picture of the political situation on the European continent. In the seething stream of “insiders” and anonymous sources, opinions, and assessments, the most important thing was lost – the facts. They, speaking for themselves, did not even recede into the background, but turned out to be completely relegated to the backyard. They “talked”, but they were interrupted and drowned out by experts and analysts, predictions and assumptions – all that has become the spirit of modern news media focused on infotainment. In other words, news with entertainment elements. After all, the audience demands a show, emotions, heated debates… Otherwise, why keep the TV – or smart TV – on?

Meanwhile, the buildup of Russian military buildup on the border with Ukraine in November-December 2021 did not go unnoticed by both world and domestic media. Stop words did not yet exist, and therefore mentions of a “possible “invasion”” on media websites (in this case, RBC) were commonplace, part of the agenda.

Back then, journalists asked direct questions, not thinking about the laws on “fakes” and “discrediting”. However, the responses of the officials of the Kremlin apparatus rather exacerbated the cognitive dissonance. “Such headlines are nothing but empty and unfounded escalation of tension. Russia poses no threat to anyone,” Dmitry Peskov said, commenting on US media reports about the impending invasion.

“Empty and unfounded escalation of tension” now seems especially absurd from the lips of Dmitry Peskov. However, even Vladimir Putin admitted that Peskov’s mouth “sometimes produce such a bullshit.” And this is the mouth of his press secretary.

The Russian media space until February 24 was a pre-war media chaos built stage-by-stage, from which it was not at all easy to assemble a sane and logically understandable picture of the world. Surely, the pre-war agendas of the Russian media will be the subject of close scrutiny. However, there are already materials documenting the false statements of Kremlin officials. One of them appeared on February 24 on the Russian-language DW website: “Putin lied that there would be no war with Ukraine. Chronology of deception of the President of the Russian Federation.” In addition, the very statements that turned out to be undisguised lies and deceit on the 24th are still in the public domain and cause internal dissonance (example below):

Now looking back at the past, one can be surprised and ask oneself: “could there have been doubts?” But just the same doubts were sown: the statements of the country’s top officials differed from the information of the intelligence services of foreign special services, and the negotiation process did not stop even at the moment when “demands”, or rather an ultimatum, appeared on the table… Nevertheless, a storm was approaching, dark and potentially destructive, but due to human faith in the best, the opposite – the worst – is hard to believe.

On the morning of February 24, the sounds of air raid sirens and rocket explosions fired from the Russian army were heard on the territory of Ukraine. There could no longer be three opinions, there were only two, mutually exclusive. Those who were without an opinion, of course, were cunning, but sat out, fearing a hail of sanctions that did not bode well for the largest country in the world.

On February 24, the coverage of military operations in Ukraine was divided into two vectors – the recognition of aggression and its denial. Liberation and capture. A movement towards the world and a movement away from it. This antonymy of meanings reveals the gravity of the challenge that objectivist journalism now faces—the challenge of denying facts, verifiable reality, and the very existence of truth.

Be that as it may, the information flow covered both banks. And on the Russian one, in order not to provoke a wave of panic, indignation, and fear among the population, to hide irrefutable evidence of crimes, to take control over the facts, the Russian government erected a “media dam” in the form of legislative drafts on “foreign agents” and “discrediting”. In other words, military censorship was introduced in Russia.

Military censorship and the propaganda truck

After three months of military censorship, it is becoming more and more difficult to imagine the time when these same forbidden words – war and invasion – were printed in various publications in the Russian Federation. After February 24, for several days, the authorities quickly developed the laws on “foreign agents”, as well as on “fakes” and “discrediting” of the Russian army. Any message in any form began to carry the prerequisites for a criminal term with imprisonment up to 15 years.

Such measures were the reaction of the Russian authorities immediately to a number of events that occurred in the first days of the invasion of Ukraine:

- The coverage of events in Ukraine by the opposition and not positioning themselves as opposition, but pursuing the rules of objectivist journalism, ran counter to the official version of the Kremlin, and therefore posed a threat (see below for why);

- The wave of protests against the invasion of the territory of Ukraine could potentially develop into protest movements of the scale of 2011-2012;

- Social networks have long been a place to bring people together, and exchange information and opinions – everything that could contribute to the growth of protest moods (and therefore Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter were blocked by Roskomnadzor).

Without total power over the media and Internet spaces, the Russian government had no tools of control and intimidation. There was even an uncoordinated, single rebellion on Channel One, which was live broadcasted! Military censorship became that tool.

Such a step actually destroyed all chances for the existence of objectivist journalism on the territory of the Russian Federation. Moreover, censorship, which destroys any publication objectionable to the pro-government interpretation of events, has turned the Russian audience into a kind of hostage to Kremlin propaganda. And it’s not just about the media. And the beginning of this trend was laid at least 10 years ago. “After the dispersal of the rally on Bolotnaya, a real reaction began – the decision to ban everything, destroy political competition, squeeze out all those who disagree,” said opposition politician Dmitry Gudkov in an interview with DW.

Over the past decade, many have become accustomed to persecution, persecution, restrictions, and prohibitions. Got used to it. And they even accepted it, forgetting if it could be any other way.

Although it would seem, the very fact of such censorship should have rather alerted the audience, absorbing only one narrative chewed for the end consumer. It is swallowed mechanically and without hesitation. There are several reasons: 1) the “forces” of propaganda acting from all sides, guaranteeing the dominance of a single information field, 2) the cultural characteristics of media consumption (most people are interested in entertainment content), 3) the key role of the media in assigning legitimacy. Many of these principles were formulated more than 20 years ago by such researchers as D. McQuail, W. Gamson, D. Crotier, and W. Hoynes. However, it is not enough just to swallow the narratives; it is important for the voices of the Kremlin to influence – to reach the hearts of the crowd. With such massive and uncontested pressure, it is not so difficult to do this.

More devastatingly, military censorship has set in motion mechanisms of self-censorship, spirals of silence – any opinion that contradicts the majority often remains unspoken. Weighing the risks and consequences, a person – be it an ordinary citizen or a journalist – unwittingly becomes a hostage to a system where the will is at stake in the literal and metaphorical senses.

With the adoption of the aforementioned laws, Russian media and those that carried out their activities on the territory of Russia had a very limited choice: either closure, or trial, or “play the Kremlin’s tune” – directly or indirectly. Many from the “blocked list” – for example, the BBC, Deutsche Welle, Euronews, Important Stories, Meduza, and others – continued their activities, but with one caveat – outside of Russia. Other media that have adopted the new rules (RBC, Gazeta.Ru, Kommersant) collect material about the Russian invasion under the headings “Military operation in Ukraine” or “Operation in Ukraine”. Some editorial offices, such as Kommersant or Nezavisimaya Gazeta, even dare to rebel and express opinions that are extremely unpopular in the Russian media environment, but such journalistic antics are akin to an essay by Timothy Snyder in The New York Times. Even if they cause resonance, in essence they remain solely the opinion of the author of the publication, and not the position of the editors.

The long “arms” of Roskomnadzor, the body responsible for restricting the rights of free speech in Russia, have been untied and are controlled by the head office in the Kremlin. By the way, no one has ever had any illusions about a supervisory body designed to maintain a balance of points of view in the Russian media space. Roskomnadzor appeared as a devoted Cerberus in 2012 in unison with the return of Vladimir Putin to the presidency, and now, having broken the chain, it inspires fear – fertile ground for propaganda and internal censorship.

The expulsion of objectivist journalism from the Russian Federation, the tightening of legislation restricting freedom of speech and opinion, as well as the ever-increasing control in the Internet space (including the blocking of uncontrolled social networks) – all leads to the fact that the Kremlin, its statements and interpretations of events, become the bearer of unshakable “truth”. Any attempt to sway is punishable by law. And the law itself inspires fear, sows doubts in the minds of Russian citizens about the existence of reality (where are the facts, and where are the lies), and ultimately brings chaos. In turn, doubts and the inability to independently understand what is happening are the necessary conditions for manipulating public consciousness with the help of the latest propaganda techniques, the mouthpiece of which is the current Russian media.

Others, alas, no longer exist in Russia.